By: Nicholas Sherwood and Oakley Hill

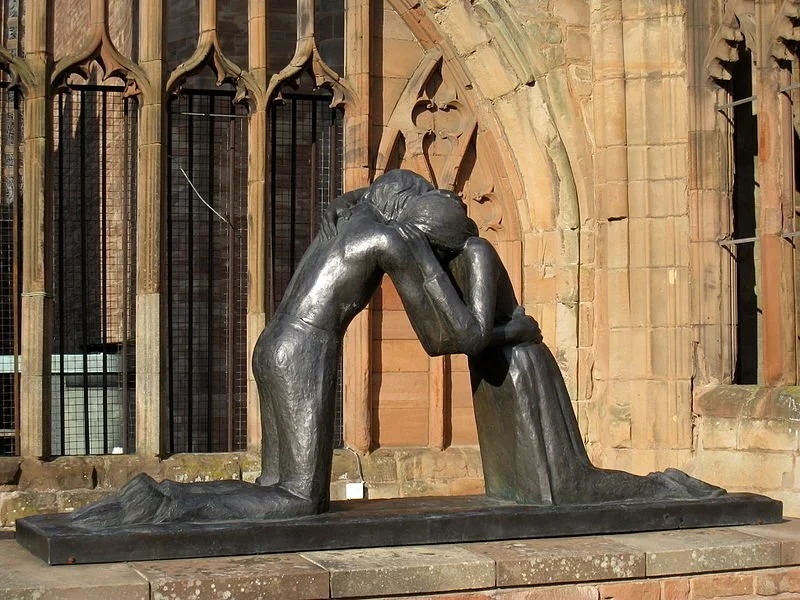

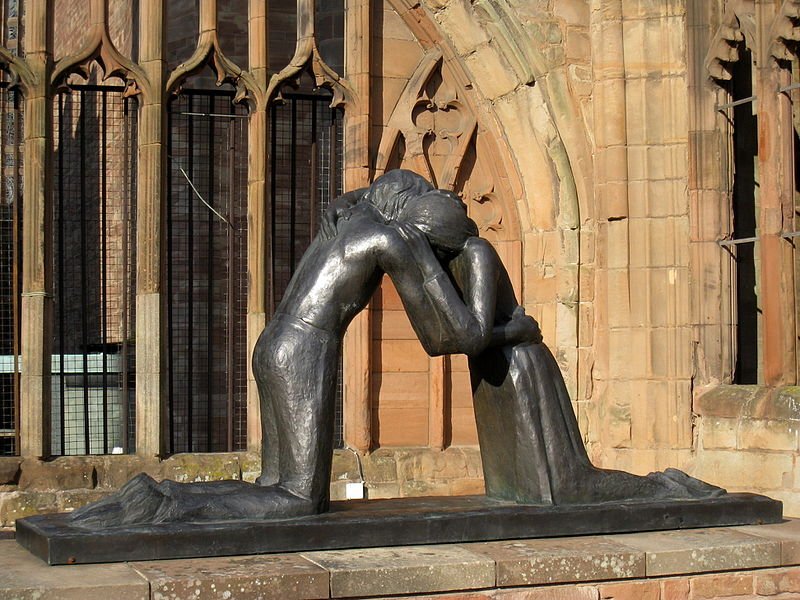

Photo credit: “The sculpture ‘Reconciliation’ by Vasconellos, Coventry Cathedral” by Martinvl. Creative Commons.

Since the summer of 2020, MHCR researchers and affiliates have conducted a two-part review of primary and secondary data surrounding how, when, and why reconciliation theories of change (ToCs) have been used in international reconciliation practice. This project, commissioned by the United States Institute of Peace (USIP), sought to support the ongoing work of USIP’s Senior Expert, Reconciliation, Dr. Carl Stauffer. Dr. Stauffer, former faculty member of Eastern Mennonite University’s Center for Justice and Peacebuilding, leads a team of staff at USIP that seek to delve into the nuance of reconciliation through transformational practice and research. In the past two years, USIP has sought to conduct an ‘evidence review’ of all its primary peacebuilding practices (e.g., mediation, arbitration, negotiation, and reconciliation). These evidence reviews seek, at base, to understand what works – and what doesn’t – about basic processes in peacebuilding.

To prepare for this review, MHCR staff Oakley Thomas Hill and Nicholas R. Sherwood prepared an overview of key theories and literatures on the various levels of reconciliation: within and between individuals, within and between groups, within and between societies / countries, and deep structural factors. USIP then contracted MHCR to complete a two-phased review, examining: (1) reconciliation program designs and evaluations that specifically included theories of change in their work and (2) surveys with reconciliation practitioners focusing on their experiences deploying ToCs in the field. Below, we have summarized key insights from this research project in the hopes of making our research freely available and actionable for reconciliation practitioners.

Finally, we wish to thank the contributions of Michael (Mike) Sweigart (Carter School PhD student), Amelia Johnston (Carter School BA and MHCR alum), and Kelsey Vaughn (MHCR alum) for their contributions to this project. A core driver of MHCR’s research and practice is our desire to train the next generation of reconciliation researchers and practitioners; by including students in opportunities like these, we hope our students and ‘seasoned’ professionals are able to cross-pollinate their wisdom, experience, and passion surround transformative reconciliation.

Phase One: Reconciliation Theories of Change and Their Utility in the Field

A theory of change (ToC) is an attempt to hypothesize how, when, why, and through which mechanism(s) a given intervention will alter a conflict context. Most theories of change are structured according to the following formula: “If a, then b, because c”. This structure mimics statements used during hypothesis-testing in line with a positivist, empirically-grounded approach to social science. In other words, many theories of change hinge on deductive reasoning, whereby a given hypothesis is tested through the deployment of specific measures, instruments, and analytic tools. Furthermore, for the purposes of this report, reconciliation refers broadly to bringing people together after violence (widely defined) has occurred. Reconciliation processes vary widely, ranging from interpersonal reconciliation (e.g., relationship-building between individuals and groups who may have committed acts of violence against one another) to political reconciliation (e.g., implementing policies aiming to reduce inequality between conflicting groups). Furthermore, reconciliation processes are contextual affairs; reconciliation tactics and strategies vary according to the type of violence and conflict between two or more conflicting groups, according to cultural mores and practices, according to political and cultural buy-in, and according to the amount and intensity of resources available to reconciliation practitioners.

To better understand the challenges of deploying reconciliation ToCs, our team conducted a meta-synthesis of ToCs utilized for reconciliation processes within a variety of global conflicts. A meta-synthesis features two main ingredients: (1) the systematic collection of a given literature (e.g., scholarly publications as well as gray and white literatures) and (2) a qualitative analysis of difference (and by extension, sameness) between these literatures.

Specifically, our team collected and analyzed twenty-one (21) theories of change utilized within reconciliation processes. These ToCs were deployed by NGOs and GOs operating within a wide range of conflict contexts, largely within communities not presently experiencing violence (i.e., post-conflict reconciliation). As noted above, the depth in which each ToC was interwoven into each intervention varied widely; some interventions directly tested the accompanying theory of change, while others included a ToC but only reported activities (e.g., how many meetings were held or how many participants were trained). Additionally, while most items represent the final monitoring and evaluation report submitted to the grantor of an intervention program, some items were summary reports conducted during an intervention (e.g., a six-month or one-year report). At the end of this report (Appendices A and B) is a list of each reconciliation ToC our team gathered and analyzed as well as the websites from which they were gathered.

Based on our findings, reconciliation evaluations featuring programmatically-tested ToCs share four general traits: (1) they address relationship-building in peri- or post-conflict contexts, (2) they employ mixed-methods approaches to testing said ToCs, (3) they generally occur in Africa and Southeast Asia, and (4) they utilize proxy measures of evaluation (e.g., cognitive readiness to reconcile) to understand how, when, where, why, and between whom reconciliation is more likely. Evaluations testing ToCs are not largely different from evaluations with untested ToCs; it is likely the case that habits and histories of funders (e.g., donors, foundations) and peacebuilding organizations shape said organization’s willingness to both deploy reconciliation ToCs in the field and their readiness to test these ToCs throughout a program’s lifespan. With regards to reconciliation evaluations that did not include ToCs, few if any unifying themes emerged from our team’s analysis. Clear, concise, and testable indicators often ‘reign supreme’ in many reconciliation programs; therefore, reconciliation organizations who believe deploying ToCs may supplement, explain, or deepen these indicators may be more likely to utilize ToCs in the first place.

Phase Two: What are Reconciliation Practitioners Saying?

The second phase of this project consists of primary qualitative and quantitative data collected from United States Institute of Peace (USIP) staff and referrals from USIP staff between the period March and May 2022. This study consisted of participants (n = 30) completing an online survey focusing broadly on how participants utilized reconciliation theories of change (ToCs) within peacebuilding and reconciliation practice. Surveys featured quantitative items (e.g., Likert scales) and qualitative items (e.g., free response). Participation requirements include: age 18 or older, fluent in the English language, and currently or formerly work(ed) on reconciliation programs. Finally, participants are or were formerly considered ‘programmatic staff’, which does not include roles such as administrators, finance staff, or research staff. TABLE 1 provides a full breakdown of participant demographics. Highlights include: (1) a vast majority of respondents have worked in the reconciliation field for 12 years or longer, (2) participants hailed from at least 17 different countries, (3) participants work in at least 13 different countries, and (4) at least 8 women and 17 men respondents.

The results of our survey provide insights into the use of ToCs by a small but diverse range of reconciliation practitioners. Most of the participating practitioners have worked with ToCs for several years, albeit with varying frequencies. Among the minority of respondents who indicated not using ToCs, (1) lack of knowledge of ToCs or (2) practical know-how for their application were the most cited reasons. These results indicate, while ToCs are widely used among reconciliation practitioners, a lack of professional training on ToC types and how to use them may drive uneven use among practitioners. Thus, education and training on how to use ToCs may be an effective approach to increasing their use. However, it is also possible the frequency of ToC use could vary based on specific job responsibilities or cultures among different project teams at USIP. In future studies, questions regarding the relevance of ToCs for practitioners’ roles and their level of use among their close colleagues and team members may provide further insights into varying levels of ToC use.

A lack of sufficient training on ToC use may show heavier use of ToCs during the project design stage relative to the remainder of the project cycle. Although ToCs are important for the project design stage, it is also important to revisit the ToC throughout the implementation process to guide reflection, continually assess the ToC’s relevance, and adapt the ToC as needed. Further, the low level of ToC use at the project endline is problematic. A lack of critical evaluation of the ToC at the end of the program hampers evaluative learning and the gathering of evidence regarding the utility of a particular ToC. It would be useful for future studies to gauge the reasons for different levels of ToC use throughout the project cycle. While a lack of know-how may be a key reason, time, and resource constraints, as well as donor incentives, may also be contributing factors.

Moving Forward

As our team recommended to USIP in our final report: our analysis of reconciliation ToCs identified three fundamental issues. First, there seem to be competing needs in the evaluative process that are difficult to reconcile. On the one hand, evaluations are activity reports that function to keep practitioners accountable to the donors and institutions who invest in them. On the other hand, evaluations proport to test a theory’s empirical validity, thereby contributing to an ontology of reconciliation. These functions are distinct and, in some circumstances, may be exclusive. Second, most ToCs contain a single contingency statement (i.e., an “if” statement) that relates to the program’s primary method of intervention (e.g. dialogue). Because peacebuilding and conflict are complex, it is doubtful whether a single contingency statement adequately reflects what is being tested, nor does it reflect the complexity of the conflict environment. Third, some programs claim to be reconciliatory, but do not bring people in contact after violence has occurred. While there is no consensus about what is and is not included under the umbrella term “reconciliation,” most definitions implicitly or explicitly infer contact. Hence, it is unclear whether some programs are using the term “reconciliation” in a merely perspectival sense—i.e. they may be ‘writing’ reconciliation onto actions like a marketer brands a product rather than ‘reading’ reconciliation from their activities like a researcher describes an object.

Portions of this News Article directly cite MHCR’s final report to the United States Institute of Peace, which has not yet been published externally. If you are interested in reading this report, please contact MHCR Associate Director Nick Sherwood: nsherwo@gmu.edu