By Nicholas R. Sherwood

Introduction: The Need for Peacebuilders vs. Care for Peacebuilders[A1]

Many [A3] practitioners find mental health / psychosocial support (MHPSS) is a dimension too often undervalued and overlooked within the peacebuilding field. Within the peacebuilding context, sound mental health is most often subverted by the accumulation of heavy stressors (e.g., exposure to violence, job-related frustrations, deprivation of resources) across an extended period of time (Orrnert, 2019). Over time, these stressors compound, placing the peacebuilder at a heightened risk of poor mental health, isolation and lack of psychosocial support. A recent, pre-COVID, survey highlights the following statistics about MHPSS within humanitarian aid workers: (a) 91.4% of respondents reported a traumatic event during their service, (b) 10.1% report symptoms of depression, (c) 3.6% filled psychometric requirements of a post-traumatic stress disorder diagnosis, and (d) women aid workers are placed at a much higher risk of MHPSS challenges than men (Borho et al., 2019). In the context of peacebuilding and exposure to conflict zones, MHPSS challenges are deeply intertwined with behavioral issue as well, including vocational burnout, withdrawal from one’s friends and family, and substance abuse and dependence (Jachens, 2019). Even prior to the COVID outbreak, many MHPSS professionals made calls for mental health researchers to turn their gaze to the massive challenges of peacebuilding and humanitarian aid (O’Donnell, Picoke & O’Donnell, 2020).

The fissure between the need for peacebuilders and care for peacebuilders can have significant consequences, especially if peacebuilders are expected to stay in a conflict context for an extended duration and whose presence is critical for operational success. This gap has been widened by COVID in several keyways, including (a) the marginalization of peacebuilders testing positive for COVID, (b) lack of access to personal protective equipment, (c) increased violence in the field, and finally (d) women peacebuilders’ experiences of inequitable access to care and expulsion from their field sites (Sharma, Scott, Kelly & VanRooyen, 2020). The question now becomes: What can be done to help peacebuilders build psychosocial support during the COVID pandemic?

MHCR Task Force on the Psychosocial Support for Local Peacebuilders During COVID

To answer this question, MHCR convened an emergency Task Force centered on providing psychosocial support for peacebuilders during COVID (PSPB Task Force). The Task Force is co-led by Annalisa Jackson (MHCR Associate Director) and Rowda Olad (MHCR Reconciliation Fellow) who direct three workstream coordinators, Aimee Lace (PhD candidate, Teacher’s College, Columbia University), Angelina Mendes (PhD candidate, Carter School), and Nick Sherwood (PhD student, Carter School), and features the following members: Antti Pentikäinen (MHCR Director), Dr. Cherie Bridges Patrick (Paradox Cross-Cultural Consulting, Training and Empowerment), Paula Donovan (practicing social worker), Dr. Michèle Lewis O’Donnell (World Federation of Mental Health), Pat Drew (senior executive coach, social worker), Manal Tayar (Duke University), and Chip Hauss (MHCR Visiting Scholar). Over the course of two months, the PSPB Task Force met virtually, consulted with local peacebuilders coping with the fallout from COVID, and hatched a response plan to care for these peacebuilders. Emerging from these discussions is a multi-tiered support mechanism, ranging from low to high involvement with regards to frequency, duration, and intensity of required support:

Tier 1 Online Resources: Low Support (coordinated by Nick Sherwood). This Tier includes an online resource database with popular and academic literatures on peacebuilding, COVID, and psychosocial support; ‘alternative’ resources, such as podcasts, video blogs, and webinars; and contextual information for peacebuilders operating in certain cultural, linguistic, and religious spaces. This information will be published on the MHCR website and will be widely available.

Tier 2 Organizational Support: Medium Support (coordinated by Aimee Lace). This Tier primarily features learning exchanges among peacebuilding organizations as well as training sessions and information for organizations working with, supporting, or employing peacebuilders. These learning exchanges and trainings include knowledge related to burnout in the workplace, the specific stressors brought about by COVID / COVID response externalities, and the importance of psychosocial support for individuals in the ‘caring professions’.

Tier 3 Peer Support: High Support (coordinated by Angelina Mendes). A pilot Peer Support Program has been launched to foster virtual spaces of peer support during challenging times of Covid-19. Peer support groups are led by experienced facilitators and foster a space of self-reflection, mutual learning and growth. More information can be found here.

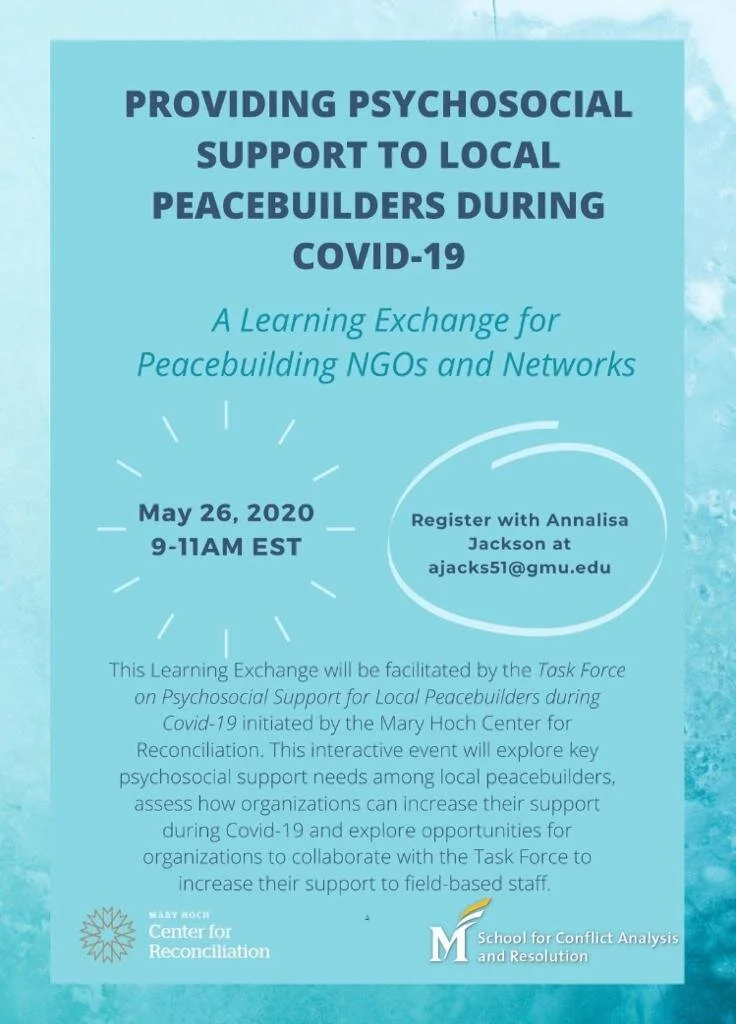

Learning Exchange, 26 May 2020

To ground the Task Force’s assessment and plan of action, on 26 May 2020, we convened a Learning Exchange for Providing Psychosocial Support to Peacebuilders during COVID-19. The Learning Exchange featured representatives from nearly 40 peacebuilding NGOs, academic centers, and peer networks; each representative possessed first-hand knowledge and exposure to the impact of COVID on the lived experience of peacebuilders operating in conflict zones around the world.[1]As discussed above, peacebuilders and others in the healing professions experience undue physical and psychological toll as a direct result of their work – this toll has been massively compounded with the outbreak of COVID and subsequent loss of support in almost all sectors of a peacebuilders’ life. The Learning Exchange offered a powerful opportunity for these peacebuilders to relay their specific, grounded needs to MHCR’s Task Force and commune with other peacebuilders from around the world on these issues.

Prior to the Learning Exchange, MHCR released a survey to create a baseline needs assessment of peacebuilding organizations coping with COVID.

key findings included:

Isolation and anxiety were ranked as the most prevalent psychosocial challenges during Covid-19. Trauma and depression were also reported but as less prevalent

The most prevalent organizational challenge to delivering psychosocial support was internal capacity to plan and deliver services.

The least prevalent organizational challenge to delivering psychosocial support was a lack of resources.

54% of staff were reported to have reliable internet, 43% reported having unreliable internet and 3% reported having no internet.

Following the review of this information, local peacebuilders from Afghanistan, Syria and Somalia recounted the risks and challenges with COVID in the field. These speakers highlighted the following points:

High need for increased communication within and between peacebuilding networks / organizations on (1) the need for bolstering psychosocial support mechanisms for staff, (2) challenges organizations are experiencing providing this care, and (3) specific and tangible solutions to overcome these challenges.

Organizations should defer to local peacebuilders for solutions to the crisis (i.e., these individuals are deeply imbedded within the cultures in need of transformative change).

Media must be mobilized to fight COVID in conflict zones (e.g., using radio programs to alert populations to COVID hotspots and best hygiene practices).

High need for greater remote capacity building and mentoring.

High need to engage with peacebuilders working in conflict zones amidst COVID.

In an effort to ground the response protocols for these needs, Task Force members Cherie Patrick-Bridges, Michele O’Donnell, and Aimee Lace then sketched the conceptual underpinnings of the Task Force’s efforts to empower peacebuilders during COVID. Their reflections highlighted the importance of contextualizing psychosocial support and focusing on the totality of health experiences. The need for organizations to take responsibility for providing support to peacebuilders and adapting a “Philosophy of Care” was highlighted. This kind of support can be distinguished through a tiered approach that differentiates levels of support according to frequency, duration and intensity[A4] .

Learning Exchange participants broke into several small group discussions to highlight prevailing psychosocial challenges as well as organizational best practices and lessons learned for providing psychosocial support to local staff and affiliates. Discussions highlighted the challenges of insecure funding, insufficient organizational bandwidth to focus on bolstering psychosocial support, misinformation, sociocultural stigma around psychosocial support, isolation, family responsibilities, burnout and other various challenges. Key lessons learned that were noted included: constant and efficient communication from organizational leadership about the importance of psychosocial support, trauma awareness training, spiritual and religious practices, and organizational forums to build trust and discuss the effects of the pandemic on individual staff.

Many participants noted the ongoing challenges they faced within their organizations to provide psychosocial support to staff included: providing equitable access to services, unstable internet connection, lack of funding, gendering of psychosocial care (i.e., ‘therapy is for women’) and other contextual factors (e.g., linguistic, religious, spiritual cultural needs).

Small group discussions were followed by a brief presentation of Task Force services by lead coordinators Nick Sherwood, Angelina Mendes, Manal el Tayar, Aimee Lace, and Antti Pentikäinen highlighting the key workstreams led by the Task Force as the upcoming pilot Peer Support Program.

Presentations by Katie Mansfield (STAR Director at Eastern Mennonite University) and Musarrat al-Azzeh (Associate Director Center for Mind Body Medicine) also introduced key resources including the Strategies for Trauma Awareness and Resilience program and trainings through CMBM.

Finally, Annalisa Jackson offered concluding remarks and thanked participants for their contributions to the Learning Exchange.

Psychosocial Support of Peacebuilders: A New Frontier in Our Field?

Throughout my conversations within the Task Force, my involvement in the Learning Exchange, and my experience as a peer support facilitator for peacebuilders coping with COVID, I am awed by the resilience and tenacity of peace practitioners. We must remember, despite the litany of needs and challenges peacebuilders face during this time, these individuals and their communities are actively creating coping and dealing strategies to protect themselves from the twin dangers of COVID and pre-existing conflicts. Peacebuilders, in many instances, call upon culturally-grounded / indigenous resources to assay these dangers, building deep and wide networks of support and empowerment. Despite the challenges our global community is currently facing, it is critical our Task Force and other support networks honors the ingenuity of peace practitioners. Our role is not to merely offer guidelines and protocols for self-care; instead, the Task Force’s role is to understand our peacebuilding partners’ existing psychosocial support strategies, empower these strategies to the best of our ability, and facilitate communication between peacebuilders for knowledge-sharing. Programs like the Learning Exchange allow for these types of interaction – virtualized and trans-border, bridging between scholars and practitioners, and an empathic space to allow vulnerability.

As a member of MHCR’s Task Force and a scholar-practitioner of mental health empowerment, there is little doubt in my mind the peace and conflict studies field is in need of a new turn. As the global community copes with COVID, and as peacebuilders bravely enter the fray to heal their communities and loved ones from pre-existing conflicts exacerbated by COVID, it is critical our field bears witness to the struggles and victories of peace practitioners. In my eyes, peacebuilders are heroes. Our field, a vanguard of peace, justice, and human rights, has an ethical obligation to care for practitioners – the front-line workers of the theory and method we cultivate on issues surrounding peace and conflict. The challenges of COVID, as exemplified by testimony from peacebuilders affiliated with MHCR’s Task Force and participating in our Learning Exchange, highlight a lacuna in our discipline: the role of mental health / psychosocial support for practitioners operating in conflict contexts. Learning Exchange participants were unequivocal in their call for an invigorated research and intervention program to support the psychosocial health of practitioners, and I believe our field has both the heart and smarts to answer their call. This new turn towards mental health in peace and conflict studies has the potential to reshape how we view conflict within each individual and how this experience intersects with contexts of peace and violence. By centering the experiences of practitioners in our investigation of mental health, we may yet sketch new frontiers of transformation, frontiers defined by resilience, empowerment, and bolstered quality of life. Investing in this new turn in our field benefits not only practitioners, of course. In the words of one Learning Exchange participant: “supported people support people”.

References

Borho, A., Georgiadou, E., Grimm, T., Morawa, E., Solbermann, A., Nißlbeck, W. & Erim, Y. (2019). Professional and volunteer refugee aid workers-depressive symptoms and their predictors, experienced traumatic events, PTSD, burdens, engagement motivations and support needs. Environmental Research and Public Health, 2019(16), 4542-4558.

Jachens, L. (2019). Humanitarian aid workers’ mental health and duty of care. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 15(4), 650-655.

O’Donnell, K., Pidcoke, H. & Lewis O’Donnell, M. (2020). Engaging in humanity care stress, trauma, and humanitarian work. Christian Psychology Around the World, 14, 153-167.

Orrnert, A. (2019). Implications of not addressing mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) needs in conflict situation. UK Department for International Development.

Sharma, V., Scott, J., Kelly, J. & VanRooyen, M. J. (2020). Prioritizing vulnerable populations and women on the frontlines: COVID-19 in humanitarian contexts. International Journal for Equity in Health, 19(66), 1-3.