By: Hannah Adamson

“Reconciliation, as I see it, is people baring their heart sheds. It is not easy...it is a process, it is not something that can be forced” shared Betty Bigombe during a call with Antti Pentikäinen, MHCR Director, and Hannah Adamson, MHCR Research Assistant.

Betty Bigombe is one of the most internationally renowned women mediators from Uganda. She has served in various roles within the Ugandan government and is known for her crucial work in bringing Joseph Kony, leader of the Lord’s Resistance Army, to peace talks during the early 1990s. She has also worked within the World Bank and is a Senior Fellow at the United States Institute of Peace. Currently, Bigombe is also a Fellow for Mary Hoch Center for Reconciliation. During the conversation, Bigombe shared more about her vast experiences as a mediator and what she has learned along the way.

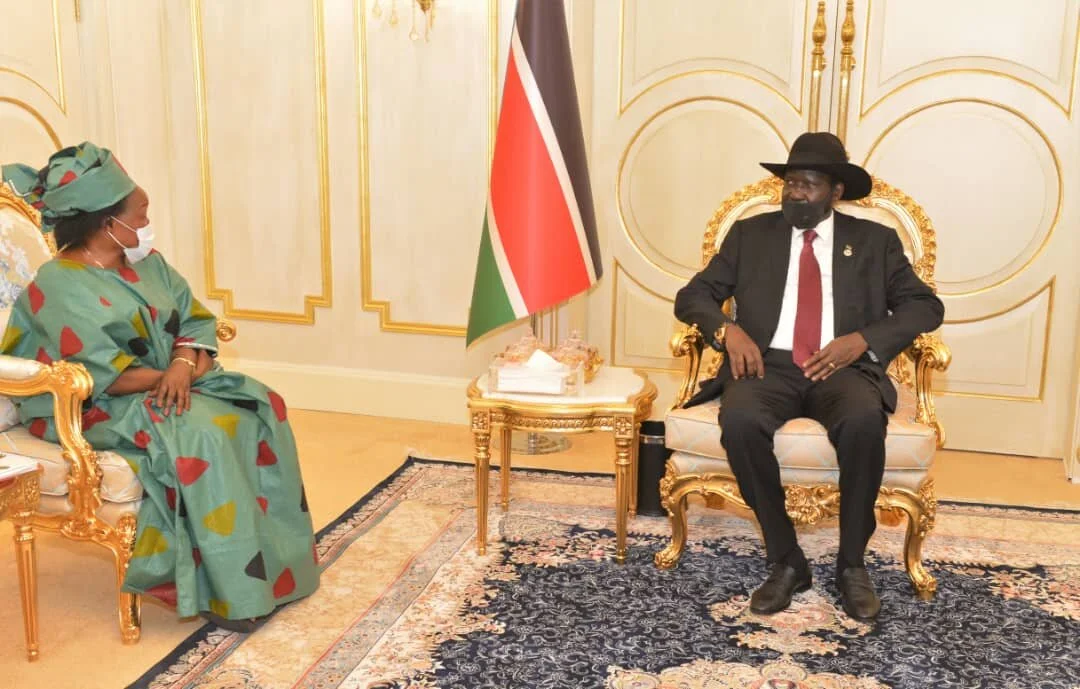

Bigombe is working as Special Envoy for the President of Uganda to the Parties to the Revitalized Agreement of Resolution of the Conflict on South Sudan (R-ARCSS). She has played an essential role in bringing President Salva Kiir and First Vice President and Sudan People's Liberation Movement-in-Opposition Leader Riek Machar together to resolve a number of pending issues necessary for the peace process. For example, Bigombe helped to broker the number of regional states and then followed up on details of the agreement during the pandemic to enable the National Parliament to become operational and appointments for Governors to proceed. The fragile peace process was further complicated by the outbreak of coronavirus earlier this year and Bigombe was among the few that could continue to assist the process and the nation. The pandemic did not stop Bigombe from traveling to Juba. She explained the difficulties of communicating with heads of state over the phone, as there was often no direct communication, but rather messages passed through the staff. Despite the drive typically over eight hours between Uganda and Juba, South Sudan, Bigombe has traveled back and forth to facilitate meetings and continue discussions about implementing the peace agreement even during the pandemic.

Bigombe emphasizes the important role of women and community members in peacebuilding. During her work in Northern Uganda, Bigombe stayed in camps for internally displaced people, shared meals with them, and listened to their stories. She shared the essential role that grassroots women played in suggesting solutions and providing ways for her to connect with violent parties. Bigombe highlights these local women as “unsung heroes” within peacebuilding efforts. Considering the influential role of local actors in peacebuilding within Uganda, Bigombe has advocated for the inclusion of community and cultural leaders in the peace process in South Sudan. She received approval from President Kiir to pursue ways to bring representatives from South Sudan’s sixty-four different tribes to Juba to host discussions on National Dialogue. Bigombe explains how these tribal leaders have an essential role to connect with community members, especially those involved in the violence, and move them toward reconciliation.

While talking about her experiences over the years, Bigombe emphasized the importance of hope. This is not to say she has not experienced daunting challenges in her work. During her time working to broker peace with the LRA, Joseph Kony committed mutilations against civilians and had them deliver her letters stating he was not interested in peace. Despite continued serious risks to her personal safety, Bigombe persevered to move beyond scare tactics towards significant change. Throughout her years as a peacebuilder, she has also experienced doubts about her abilities as a woman. Instead of allowing this to prevent her from fostering change, however, she has worked to demonstrate the key role women play in peacebuilding and lift up other marginalized voices. For example, she has invited a delegation of women from South Sudan to show government leaders the pain of war. According to Bigombe, their unique ability to show emotion and their roles as mothers of lost sons showed the government the “heart and soul” of involved parties.

Bigombe highlighted how change, peace, and reconciliation cannot be rushed. While the journey to peace can be long and arduous, there is hope. She described how when driving through Uganda: “Nothing brings me more pleasure than seeing schools open...their lives are no longer in danger of being abducted” and that “It gives me a lot of satisfaction to see people living in harmony, to see smiles on their faces”. Years ago, this reality may have seemed impossible, but her tireless efforts and those of other peacebuilders have transformed dreams of peace into reality. Her journey is the embodiment of resilience and illustrates what can be achieved with hard work, time, and determination. Betty Bigombe’s story and her passion for helping others can serve as an inspiration and a source of hope during times of darkness.

The Mary Hoch Center for Reconciliation is excited to be supporting Betty Bigombe’s work in South Sudan and Uganda. We are committed to supporting insider-reconcilers, like Bigombe, through fellowships, mentorship, sharing connections, and research support. When we unite to foster reconciliation efforts, we have the potential to foster true positive change.

Betty Bigombe meeting with President Kiir in Juba, September 2020.